Nate Marshall

I’m not convinced I’m a first draft writer of much merit. I am not a particularly productive writer, at least in comparison to some of my friends and heroes. I haven’t led the most interesting or poem worthy life, though I’ve seen some things and read more things. The one part of my practice that I feel mostly confident in is revision.

Once in high school, no lie, I gave a talk to an English class about my revision process. The steps I used then are still some of my favorites. All my second drafts (on a computer) are in a block of text with no line breaks. I like doing this because, unless I’m writing in a specific form from the outset, I tend to make line breaks instinctively. The first drafts tend to have line breaks based upon whatever I thought “looked like a poem” that day. The unlineated draft is an opportunity for me to take a step back and see the language in a dressed down way. From this I like to take away unnecessary language and think about what more I might need and then I like to look for patterns or potential patterns I can revise into. I think poems often have a submerged or unconscious form so I’m trying to be attentive to that and then step into that form in a more conscious manner.

Revision is a welcome part of my process perhaps because I often assume my own error. I grew up losing (often badly) in poetry slams and rap battles. It was many years writing before I experienced much success. I’m happy (sometimes too happy) to produce many words and then throw them away. I’ve heard some describe revision as a process of killing your “darlings.” For me, with my writing, I channel the immortal wisdom of the rapper 2 Chainz: “I just call her/ I don’t know her whole name.” Put another way, these words ain’t my darling, we just kicking it.

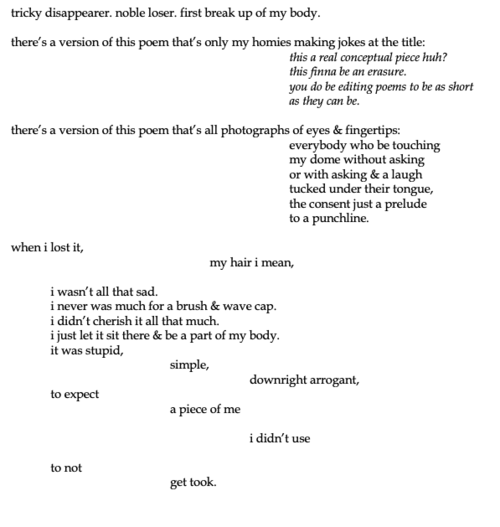

< draft 1 >

ode to my hair

< final version >

ode to my hair (reprise)

tricky disappearer. noble loser.

first break up of my body. one version

of this poem is my homies making jokes

at the title: this a concept piece huh?

this finna be an erasure. you do

be editing poems as short as you can.

one version of this poem is all pictures

of eyes & fingertips: everybody

who be touching my dome without asking

or with asking & a laugh tucked under

their tongue, the consent just a prelude for

a punchline. but when i lost it—my hair

i mean—i wasn’t that sad. it was dumb

to expect to remain untouched by genes.

Helene Achanzar

This poem began in a notebook in 2008. I was living on the top floor of a Victorian mansion in Iowa City, and each morning I’d see a man bike down my street. Though I didn’t know his name and had never spoken a word to him, out of loneliness or boredom, I convinced myself I was in love. After weeks of watching him from my window, I found him drinking coffee alone at a cafe. I sat a few tables away and scribbled some lines. I never mustered up the courage to say hello. Probably for the best.

I’ve never written a poem from beginning to end. All of my poems come from pages of handwritten phrases or voice memos that are puzzled together, which means lines from a single poem may have first been composed weeks or months apart. Revision means moving lines around with the goal of coherence. My first impulse is always to write poems in couplets. I think about units of meaning in poetry - the stanza, the line, the phrase, the word - and I find that couplets are not only a complex and crystalline way to make meaning, but they're also what come most naturally to me in drafts. Sometimes I force myself to break a poem out of couplets, but it's an intentional and often unsuccessful process.

Because I usually gather too few lines for a poem to cohere, revision also means filling in blanks. For “ICD-10 F94.0: Selective Mutism,” there were a lot of blanks to fill. Over a decade after writing this poem, I’m still startled by its gestures toward violence, how distant its themes are from its innocuous origin. Equally surprising is the way the poem’s content demanded a form in which some of the blanks refused to be filled.

*

“ICD-10 F94.0: Selective Mutism” was originally published in Jubilat.

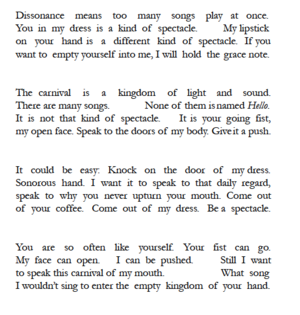

< draft >

it is pretty to think you will say hello

hello, my name is

being you must feel like the carnival

like the carnival, I have many songs

the carnival is a kingdom of light and sound

the carnival is spectacle after spectacle

you’re so often like yourself: the dissonance

of a hand against a cup

come out of your coffee

– a different kind of spectacle

I want to speak this carnival of my mouth

it’s not empty – just rest after rest

knock on the door of my dress

anything can be a door if you give it a push

you’re so often like yourself: the dissonance

of too many songs playing at once

what song I wouldn’t sing

to enter the empty kingdom of your hand

< final >

International Classification of Diseases-10 F94.0:

Selective Mutism

José Olivarez

i started writing this poem while walking to my local coffee shop. it was still cold, but the days were getting longer. it was sunny, so i turned my head up to the sky to receive as much sunlight as i could. that’s how i noticed that all the trees along my walk were blooming. the color was scarlet, so velvety i could almost feel it. i can’t explain to you why i immediately thought of my Mamá Jacinta.

another origin story for this poem is the song “Volver Volver” by Vicente Fernandez. during the spring, i got really into listening to a playlist called “Mexican Party Anthems” on Spotify. why? well, i hadn’t seen my family in over a year. my parents got sick during that time and there were some days i worried my parents were going to die, and i was going to be 800 miles away receiving the news through telephone. there’s a line in the song where Vicente sings, “yo sé perder, yo sé perder” and the way he sings it i believe it. i was trying to write a poem with that energy.

you’ll notice that there aren’t a ton of revisions. i don’t know. the most important thing i pay attention to when i’m revising can’t be fully explained. it’s a feeling. does the poem charge me with energy? might it charge others? a big part of my revision process used to be showing up to open mics and reading new work. that’s harder now, but i look forward to when i can read poems for people live again. performing helps me hear the music of the poem in a way that is tough to simulate at my desk. i cut a line because my friend Nicole suggested it to me, and as soon as she mentioned it, i could recognize the clunkiness of the line. she didn’t call the line clunky, but when i reread the poem to myself, i could hear it. i changed the word “won” to the word “taken” in the last line at the suggestion of my friend, Eloisa. i added stanza breaks to give the lines room to breathe and slow the poem down a bit. i don’t know. i might cut the stanza breaks the next time you see this poem.

< revision >

perder

sidewalks lined with branches

flashing scarlet buds & i want

to know if it’s true—my grandma

in the ground for a couple of years—

is it long enough? is it her lipstick

blushing the blooms of the trees?

or am i trying to forget

the only lesson we are required to learn:

the first loss is not the last loss

& once the losing begins

it won’t stop

until it has taken everything.

< draft >

perder

sidewalks lined with branches

flashing scarlet buds & i want

to know if it’s true—my grandma

in the ground for a couple of years—

is it long enough? is it her lipstick

blushing the blooms of the trees

that bow their heads to greet me?

or am i trying to forget

the only lesson we are required to learn:

the first loss is not the last loss

& once the losing begins

it won’t end until it has won everything.

Sara Wainscott

The early version of this poem came from taking a walk to mail a letter, walking and thinking, which maybe for most other people also involves mental gyrations between the to-do of the present and fractured flashes of memory and imaginings. On this walk, I had a fleeting moment of déjà vu, which is where this draft starts and stalls.

What fails in this draft—flailing around in time, resisting the story, and filling the moment to excess—are part of what compels my ideas about poetry. I’m fascinated by the mind-junk* responsible for these moments, the commonplace and inconsequential perceptions of daily life that accumulate into a self so personal it’s practically beneath notice, the mind-junk buzzing collectively inside human experience, mostly ignored but happening most of the time. This poem, as with all my recent poems, is shaped by a sense of simultaneity and seeking this synchronicity directs my revision process.

In reworking this poem, I wanted to double down on the things that failed initially. I attempted to explode the logic of my own story by imagining this moment within a collective hyper-compressed time blip, a portal to/through a shared experience. To that end, double-spacing the lines isolates each one to the brink of monostich, yet the syntax both suggests and blurs associations. The revision is necessarily without punctuation since punctuation interferes with this overlap. The resulting poem tries to simulcast otherwise unrelated bits of mind-junk as a subversive performance of timespace, though I know the constraints inherent to language complicate this objective. I’m okay with that. Talking about the portal opens the portal.

* trivia, memory, time, pop culture, reportage, tall tales, song lyrics, personal observation, public knowledge, signage, weather, dreams…

< revision >

revolution

The trees of time bend to the sun

I have written this before

an industrial area across the street from a post office

where consorts of joy appear

in the script

people rush toward other people

on the edge of a continent

container ships empty

crabapples fall toward the concealed

planetary core

where the multitude of undersides

finds a common point

ink presses to paper

wound shows through the gauze

speaking humanly

does not one lover belong with another

a presence contradicts a crowd

who loving contradicts

violets tangled in a rubber tire

dog chasing a demon’s tail

< draft >

vision

Once,

I saw with my mind

an industrial area across the street from a post office

where consorts of joy appeared,

white violets,

letters in a welded box.

One thing does not belong with another.

From the future I am sorting

my many wrongs,

though at the time here you were.

Liz Countryman

In a poem about memory, I am seeking something new, unplanned, possible. The collection that includes this poem started coming into being around the time I became a mother. I was experiencing, each day, how in moments of frightening, fundamental change I felt somehow in the presence of stuff from long ago, experiences I thought were lost—faced with them, now—and in this proximity to the past there was potential, like when you first meet someone you love but have not yet spoken a word.

My mother is Australian. My father is American. I grew up in New Jersey, visiting Australia once every four years or so. Green Island (Dabuukji) is offshore from Cairns, and my family went there as tourists for the day in 1984, when I was five, to see the Great Barrier Reef. This poem recalls that day trip. In 2016, I was thinking a lot about coral bleaching and the irreparable harm climate change is causing to the reef. With that wave of contemporary dread and those bright, blurry memories of visiting my mother’s home when I was little knocking against each other in my head, I wrote this first draft.

When I was first working on this poem, I found it difficult to pinpoint what made it seem unsatisfactory to me. I now recognize that there’s a kind of loose anonymity to the perspective in the early draft that leaves the poem a little cold. The speaker refers to “child,” “man,” “figure,” “body,” “anyone,” “dear one,” etc., without making those relationships specific or knowable. The tone is dreamlike and mournful, but since the poem conceals its own stakes, the reader can’t join in the mourning. To me, the poem just seemed stuck in its mood, perhaps in need of some entirely different narrative element to counterbalance the dream of memory. I rewrote the poem and gave up on it many times.

Since the first draft of the poem felt detached from the remembered experience, I revised by letting my personal attachment become more visible. The final version is more specific about physical perspective, even as it calls into question the relative position of the figures in that remembered scene. It also explores the particularity of how I carried those memories along with me months and years after. Would I have remembered that day trip, wondered about it so often, had it not been for the t shirt my father bought there? That magical, distant place became a fixture in my imagination, perhaps, by way of this familiar place—my dad’s lap, the fuzzy lettering on his shirt close to my face as I was just learning to read. The star in the final line arrived unexpectedly—a new event in the poem, not exactly something remembered. But it still seems true to me. As a child, I couldn’t think about my family without imaging this vast geographical space. Looking at that burning, distant thing—there’s a feeling of imminence, but also of miraculous proximity to the past.

*

“Green Island” was originally published in The Canary.

< draft >

Green Island

My father, wearing sneakers in the water

Or maybe another man, some stranger

Far off in the water wearing sneakers

Where the water deepens gradually stepping

Softly as on breaking flesh

The man moved slowly in a wide arc

Like a minute hand

The sea moving around him

Seemed to withdraw or thin

To go far into the reef in my sneakers

To walk from the beach

Into the crackling ocean

That recedes like a cow in a field

Is difficult and might not be allowed

I am on shore or my toes touch the water

Or I’ve been walking out a long time

Getting my sneakers wet

And still the man is distant and still the sea walks casually away

Like a cloud pulls over the sun making you think

You have done something to deserve

A brief breath of darkness

Which will end when you’ve done better

When you’ve looked correctly

Or recognized that you might deserve for a minute

To lose the sun

The island turning in the ocean

To slouch its way back towards a cool house

With a blue dirt patch under a bush

A child points at while inside the yellow windows

The grim duty of dinner organizes people

Into a family

There is a reef peeling off the island like a scab

There is a hole under a bush next to the house

A man walks on the shelf of shin-deep water in the sea

A child looks at the hole like an empty crèche

It is the man’s shelf

It is the child’s hole

The dirt underneath is alive and sore

Or rubbed thin and relieved

It’s had a bath, its hair has been washed

In the dark someone has been singing to it

All my life, like grains of sand at the bottom of a suitcase

Was this possibility

I turn away and after a while you have moved a few degrees

A dark figure backlit by bright water

Or a whitish figure surrounded by excited, blue-green water

Or months later in your soft Green Island t-shirt with the velvety writing

A velvety white sun, a boat and capital letters

The backyard darkens, I’m stirring this bluing dirt patch

The twilight persists, we’re uncovered except for trees

Looking forward as if in wind

Trying to open the eyes

The body wants to be hung up in a cradle

Back somewhere it’s already been—

To be folded carefully in a closet

So that if anyone might come back looking

It would be natural and immediate

To fall back into their hands and be plied and shushed

And hung over windows to soften light

And slid along the rim of a bowl making the air ring

Dear one, this house is where an island ends its day

And this house, with its welcoming holes

Its anxious sleep

Is made meaningful by that bright, far-off island

FIRST DRAFT BOX

FINAL DRAFT BOX

< final verSION >

Green island

My father, wearing sneakers in the water

or maybe another man, some tourist, far off in the water wearing sneakers

(that’s what they do, the coral’s so sharp)

ticks from spot to spot, and the sea

seems to be heading someplace else

I am on the shore or my toes touch the water

or I have been walking out a long time and my sneakers are soaked and still the man is farther out than me

or I’m looking at him from the water, with the island behind him, turning its back on the sea

The scene, like a cow in a field, seems to walk away without moving its legs

Where is the reef? It’s out for a stroll

Suddenly our feet are very dry

Under a bush is a cool dirt patch I stir with a finger

Inside the yellow windows my aunt and mother make dinner

The softest dirt, almost grainless

I will not have time to really go under this bush, but even as I stand here I’m hesitating

Even as I stand here I’ve had a bath, my hair has been washed, in the dark someone has been singing to me

and inside the suitcase on the closet’s high shelf are a few particles of sand

and on my father’s soft blue Green Island t shirt

is a velvety white sun, a boat and capital letters

as he sits on a lawn chair in the evening in our backyard

by the house, where the island ends its day

through our hands, as they lose shape

as a seething point, like a star.